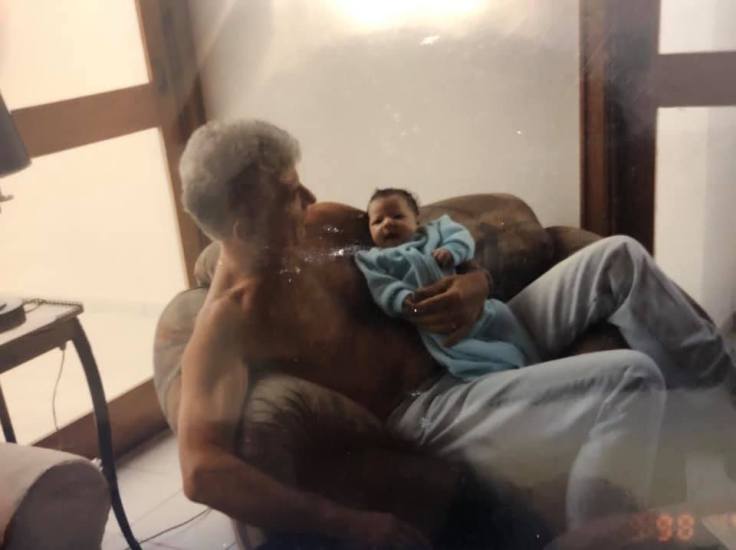

When your dad dies, there are a number of things you are expected to do, and some you are expected NOT to do. Here they are, and I’m doing them both. Reminisce, look over photos, distribute his belongings, repeat his favorite sayings, and laugh. Laugh more than you’re allowed. Laugh at things that aren’t funny. Laugh because damnit, dad, I know you’re laughing, too.

Dads and Daughters and Dances

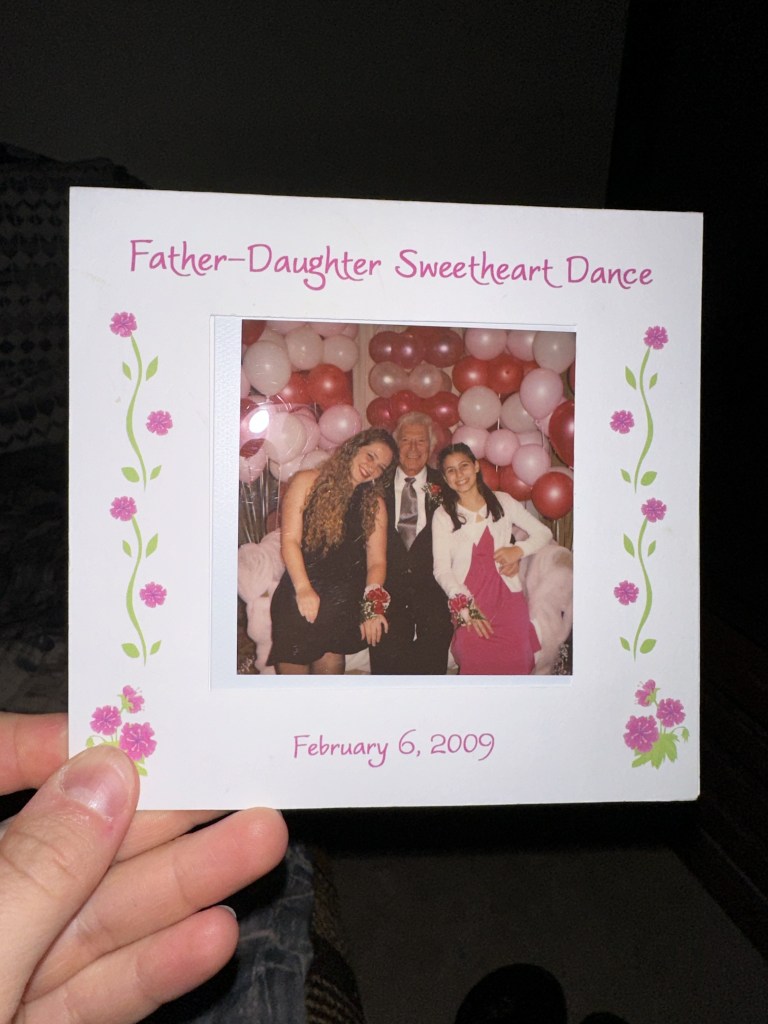

All three of us little girls screamed at the shattering of glass as my dad backed our mini van up against the next floor of the parking deck, busting the windshield. It must’ve been below freezing, because the sidewalks were slippery with ice that night.

I remember my dad yelling, “shit!” in that gruff, hearty voice of his, and my friend Camille’s dad awkwardly trying to scold the old man for his obscenities in front of the children. Allison’s dad simply kept up a positive attitude, and tried reassuring him that everything was going to be fine.

And it must have been, because no other part of that night stood out in my mind more than this incident, even though it was my first Father-Daughter dance I’d ever attended. I don’t remember what I was wearing, or if I enjoyed myself, really. I do, however, remember the dads throwing my raggedy pink and purple sleeping bag over our heads so that on our way home, flying shards of glass wouldn’t pierce our pretty little heads.

It’s funny how, looking back on that night, I obviously wouldn’t recall any sensation of weirdness about my dad. To me, it was just three dads and three daughters in a mini van going to a Father-Daughter dance. But now, the retrospection prompts questions I’d never considered before. Did the other two dads think it was weird, that the third dad was as old as, well, their own dads? Did it ever occur to Camille or Allison – “Andrea’s dad is old, really old”? Was I hoping to capture the experience of the dance with my dad precisely to hold tight to that memory, knowing it would be futile? Obviously not, I was like… seven. Nonetheless, my brain puts that pressure upon me.

The above photos were from a different year’s Father-Daughter dance, one at which my sister Sabrina was also in attendance. This was the second and final of the Father-Daughter dances I attended, and I actually have fond memories of the dance floor at this one!

The Dad Haul

The above image shows most of the things I shipped home from Florida, where dad last lived. A stack of books, featuring Stephen King, selected by Lawrence, my younger brother, the youngest brother. A big handful of watches that I hadn’t thought to look through but Pete collected because he realized half of them were technically women’s watches. Pictures of us in golf frames. A few of the golf statues I thought had a hint of fairy aura.

It seems lame, to sum him up like this. And he isn’t. Summed up, I mean. Dad’s existence certainly overflowed any and all containers, peeked out from drawers and cabinet corners. It was endless stacks of notepads, agendas, photographs, receipts, neatly organized into envelopes and shelves and boxes. There’s no way to sum up a man whose life… lives… spread across all but two continents – “I always regretted not visiting Antarctica and Australia,” he’d say – four wives, six kids, and who knows how many tens of thousands, dare I say hundreds of thousands, of people in general.

I wish I could send this blog post like a newsletter to be posted up on the corners of streets in Japan and India and Morocco and Afghanistan or wherever the hell else he went to as if to say, “DID YOU KNOW THIS MAN?” and put his photo with the blurb underneath: “WE WANT TO HEAR HOW YOU KNEW THE GREAT LAWRENCE HARVEY GELLER,” and a very official email with something like “larrygale@ fatherbiographies.com.”

This is the photo I’d use.

Bad Dead Dad Jokes

On the way to the funeral from our hotel, I’m frantically looking for conversation in the car between Pete, Lawrence, and I to distract me from the anguish and anxiety of what’s about to come. Our stepmom Arlene very thoughtfully arranged for the children to have the opportunity of an open casket before the formal, conservative Jewish funeral service. In the end, I was grateful to see him for the last time, but leading up to the moment, I was panicked.

Anyways, so we’re in Florida traffic on I-95 driving from Boca Raton to Hollywood when I randomly ask my metalhead younger brother, “Lawrence, if you could have your dream car, what would it be?” You can see where this is going.

And his dumbass, without skipping a beat, goes, “A hearse.”

I pivot in the passenger’s seat to face him with a look of suspicion and his face is staring back at me with the utmost obligatory shame, but also holding back laughter.

He went, “I recognize that that is the incorrect answer at the moment.” Pauses, hardens his gaze. “But I stand by my answer.”

I narrowed my eyes. “Are you fucking with me, man?”

Longer pause. “No. It’s just a very… goth… car.”

Needless to say, after we mournfully watched our older brothers Jay and Cristopher, our nephew Aaron, and my boyfriend Pete pick up and slide the casket into the back of the hearse… we then proceeded to giggle at one another as Lawrence croaked under his breath, “such a cool car.”

Think what you will of our tomfoolery, but I know good and well our dad was right there, laughing with us. He didn’t care about formalities. He just wanted to have a good time. And have a good time, you did, dad. Eighty-eight years, three months, and thirteen days of a good time, wasn’t it?

The Serious Stuff

Everyone keeps asking me how I’m doing. You know how we ask one another “how are you” as a form of greeting? And how none of us actually expect that the answerer will reply honestly? Having your father die, and everyone asks how you’re doing, genuinely, really makes you realize how rare it is that people are actually asking how you’re doing. This isn’t meant as a slight to anyone, so please do not take offense – rather, I want to say thank you to each and every one of you that have asked me and patiently listened for the obvious answer of “well my dad’s dead, so.”

But seriously, I actually am fine. I’m fine because everyone has given me space to grieve, to cry, to talk about random details about dad that don’t really matter to them, to tell stories that probably don’t make any sense without the context. I’ve been answering genuinely and without restraint. I’ve been putting myself in the mindset of my inner self, tuning into my feelings, and word-vomiting for however long they’ll stand there, listening.

And there is one particular thing I have been experiencing, that I in some ways feel guilt over and in other ways not at all, that I wish someone would have told me as a child was okay and not weird. That is that: this feeling, the one that starts with a pit dropping in my gut and heaving up air through my throat, the realization that he’s GONE, that he’ll never hug me or call me or write to me again, the feeling that actually prompts waterfalls – I’ve felt it before.

Is this grief? I’ve decided that this feeling is called grief. And I’ve grieved my father before.

In fact, I’ve grieved many people, many things, many concepts before that are still very much alive today, right now. I am not crazy about this, I’m realizing. It has felt very easy to accept that people grieve despite a lack of actual death.

So yeah, I grieved my dad when it dawned on me that he’s very old for a child the age of me. I grieved when he told me and Lawrence at Herbie’s diner that he and mom were getting a divorce. I grieved the day we moved out of our first house in the United States and into an apartment. I grieved every night I’d find him in front of the TV or playing solitaire at 2 AM, sleepless and depressed. I grieved when his girlfriends broke his heart. I grieved him when he moved to Florida. I grieved, angrily, every time I’d found out about a hospital visit or medical procedure after it had already happened. I grieved when I forgot to call to ask how he was doing.

And then on the night that he died, I was so exhausted from grieving the whole day, having watched him suffer with pain at the hospital, that when Lawrence woke us up in the middle of the night and said, “he’s gone,” I went, “who’s gone?” and fell back asleep.

I don’t know if I’m doing this right, but I certainly can’t be doing it wrong. I’m sorry, dad, it took you dying for me to begin to open up, but I really shouldn’t be afraid of being vulnerable anymore. Losing you was something I always expected to be one of the worst things to ever happened to me, and I’m still okay. So, I guess nothing can hurt me. Go ahead and try.

You better have a computer wherever you are in the afterlife, cause you were always the first to read and comment on my blogs!